The O’Connor Papers: A Peek Behind the Scenes at the Making of Three Supreme Court Copyright Decisions

The recently released files of the late Associate Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor reveal interesting details concerning three of the Court’s significant copyright decisions between 1984 and 1991. (See here for a post about Justice O’Connor’s copyright legacy.) Justice O’Connor (1930-2023) left her papers to the Library of Congress, which opened them to the public in March 2024. The papers provide additional insight into her thinking as she exercised her pivotal role in the shaping of Sony v. Universal (Betamax). They also increase our knowledge concerning the development of Justice O’Connor’s opinions for the Court in Harper & Row v. The Nation and Feist v. Rural Telephone. Because Justice O’Connor decided to restrict access to any files relating to a case heard by a Justice who was still serving on the Court, none of her files currently are available for any cases after October 1991, when Justice Clarence Thomas joined the Court.

-

The Ninth Circuit had found that noncommercial private home videotaping of television programs infringed the copyright in the programs, and that Sony was contributorily liable for this infringement because of its awareness that the Betamax machines it manufactured could be used to reproduce these programs. In a 5-4 decision written by Justice Stevens, the Supreme Court reversed the Ninth Circuit’s decision, ruling that consumers’ “time-shifting” of television programs was a fair use, and that Sony was not a contributory infringer because its Betamax machines were capable of a substantial noninfringing use: this time-shifting.

The Ninth Circuit had found that noncommercial private home videotaping of television programs infringed the copyright in the programs, and that Sony was contributorily liable for this infringement because of its awareness that the Betamax machines it manufactured could be used to reproduce these programs. In a 5-4 decision written by Justice Stevens, the Supreme Court reversed the Ninth Circuit’s decision, ruling that consumers’ “time-shifting” of television programs was a fair use, and that Sony was not a contributory infringer because its Betamax machines were capable of a substantial noninfringing use: this time-shifting.Justice Thurgood Marshall’s papers, when opened to the public after his death, revealed that Justice O’Connor had provided the swing vote for the Court’s decision. At the internal conference held by the Supreme Court after the oral argument in 1983, a majority of Justices, including Justice O’Connor, appeared to support affirming the Ninth Circuit’s finding that Sony contributed to copyright infringement. However, after encountering difficulty with Justice Blackmun’s draft opinion, Justice O’Connor began working with Justice Stevens, who was writing an opinion supporting reversal. Eventually she joined his opinion, and Justice Stevens had five votes necessary to reverse the Ninth Circuit.

In addition to the materials found in Justice Marshall’s papers, Justice O’Connor’s case file contains a May 19, 1982 memo from one of her clerks on whether to grant Sony’s cert. petition. The memo states that “there can be no doubt that this is a very important case. The size of the VTR industry, the use of VTR’s by millions of Americans, and the threat of the [Court of Appeal’s] decision to the industry makes this a case the Court might want to grant.” The memo continues that on the other hand, “there is no square conflict that demands resolution.” Further, “the CA’s decision in some ways does not seem unreasonable.” Moreover, “the strongest argument against granting in this case is that Congress is considering legislation to solve the problem. If the Court denied the case it would retain the option of reviewing the CA’s decision after remand. By thus postponing the review, the Court would give Congress a chance to pass legislation aimed directly at VTR’s.” The clerk concludes, “on balance, the Court might well deny at this point, in the hope that Congress will amend the copyright law before the conclusion of the remand of the case to the [District Court]. At that time, the Court would be justified in granting the case because of its importance.”

Additionally, the memo notes that twenty amicus briefs have been filed. Briefs by “retailers, VTR manufacturers, and suppliers of VTR accessories” support the cert. petition, stressing “the importance of the case to the VTR industry.” The memo refers to a brief from a group of consumer organizations “contending that the First Amendment interests of television viewers are at stake.” The memo notes that “this brief is particularly interesting because it contains a number of political cartoons inspired by the Betamax decision.” The memo mentions the amicus briefs in opposition, including for CBS, the Motion Picture Association, and associations of writers. The memo remarks that some of the amicus briefs “add a few helpful points.” The Ad Hoc Committee on Copyright Law, for example, “explains that ‘VTR’s are used to record programs for educational issues by teachers and librarians.’ The Consumer Electronics Group emphasizes that VTR’s have seemingly unobjectionable uses besides reproducing copyrighted material, such as time shifting (to permit a viewer to see a program at a different time), composition of home movies, and playing prerecorded programming on sale in various stores.”

Justice Marshall’s papers indicated that Justice O’Connor did not follow her clerk’s advice, and voted in favor of the grant of cert. Since only four Justices supported cert. (Burger, Stevens, Blackmun, and O’Connor), had Justice O’Connor opposed cert. as her clerk suggested, the Court would not have heard the case; a grant of cert. requires four votes in favor. This would have left the Ninth Circuit’s decision in place.

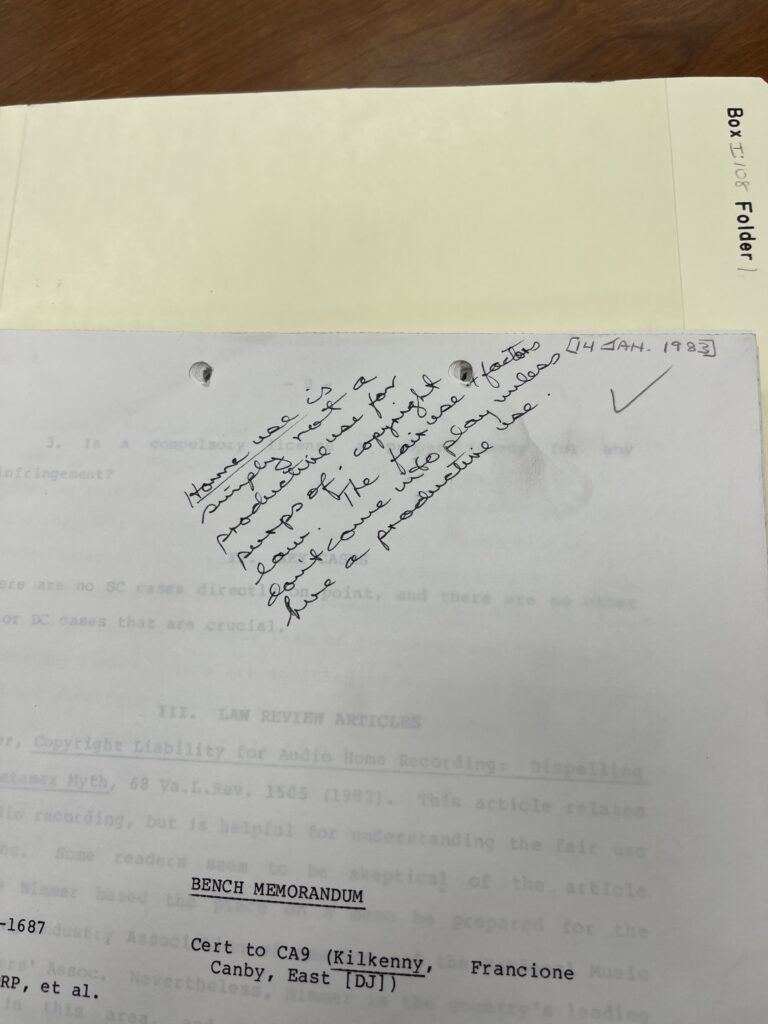

Justice O’Connor’s case file also includes a bench memo prepared by a clerk before the oral argument in January 1983. On the first page of the memo, Justice O’Connor handwrote a note that appears to summarize her view of the case after reading the bench memo: “Home use is simply not a productive use for purp[ose]s of copyright law. The fair use factors don’t come into play unless have a productive use.” This note encapsulates the fair use discussion in the bench memo, and reflects the Ninth Circuit’s discussion of fair use, as well as that of the Blackmun dissent. Justice Stevens rejected this productive use theory of fair use in footnote 40 of his opinion for the Court.

The bench memo contains other interesting remarks. The clerk notes that “this case has an unfortunate aspect and an annoying aspect.”

What is unfortunate about this case is that fair-use jurisprudence has existed quite nicely for decades with absolutely no guidance from this Court. The Court must now decide the first fair use case in its history and its decision must necessarily have some far-reaching implications for fair-use theory generally (i.e., audio recording) even though Congress will likely address the specific situation involved here by statute within the next two years….

What is annoying about this case is that contrary to popular perception, Congress was not unaware of this problem in 1976. Although Sony began to market the Betamax in 1975, Sony had been marketing a videorecorder for commercial purposes since 1965. Congress was not ignorant of the videorecorder problem. It appears as though they very deliberately avoided discussion and resolution of the problem and its fair use implications so that the courts would decide the issue.

Putting aside the clerk’s naivete about the way Congress operates, the clerk recognized an issue that persists to this day: Congressional inability to address new technologies in a timely manner.

The clerk also advised that

Although I will ultimately conclude that [Universal] should prevail, I most strongly urge that the Court not use this case as a vehicle for the examination of copyright law generally. Rather, I recommend that an affirmance of CA9 be written in a very narrow way so that the Court does not succeed in “freezing” the meaning of the fair use doctrine. Specifically, I think that the Court should state that its holding is restricted only to the blanket fair-use exemption for videorecording, and the holding does not mean that videorecording can never be a fair use or that the holding in any way applies to audio recording which, for historical and other reasons, may be treated differently.

Turning from fair use to the issue of contributory infringement, the clerk wrote that Sony and the District Court’s reliance on patent law’s staple article of commerce doctrine is “bizarre” because the videorecorder is not capable of a substantial noninfringing use. Unlike cameras and photocopy machines that are used for substantial noninfringing activity, “a VCR is manufactured, advertised, and sold to record television programming, most of which is copyrighted.”

Although at Conference Justice O’Connor took a position consistent with the bench memo in support of affirmance, she ultimately shifted sides and joined Justice Stevens’ opinion to reverse the Ninth Circuit. Given the degree to which the memo opposing cert. and the bench memo supported the Ninth Circuit’s decision, the evolution of Justice O’Connor’s thinking is all the more remarkable.

-

The Second Circuit found that The Nation magazine’s quotation of fewer than 300 words from President Ford’s unpublished memoir, including his discussion of pardoning President Nixon, was a fair use. Justice O’Connor wrote the decision for the Court rejecting The Nation’s fair use defense and reversing the Second Circuit’s decision.

The Second Circuit found that The Nation magazine’s quotation of fewer than 300 words from President Ford’s unpublished memoir, including his discussion of pardoning President Nixon, was a fair use. Justice O’Connor wrote the decision for the Court rejecting The Nation’s fair use defense and reversing the Second Circuit’s decision.The decision has been criticized for rejecting the fair use defense even though The Nation copied fewer than 300 words from a lengthy memoir. Justice O’Connor’s papers stress the degree to which she, and other members of the Court, were influenced by the fact that The Nation reproduced verbatim quotations from an unauthorized pre-publication copy of the memoir.

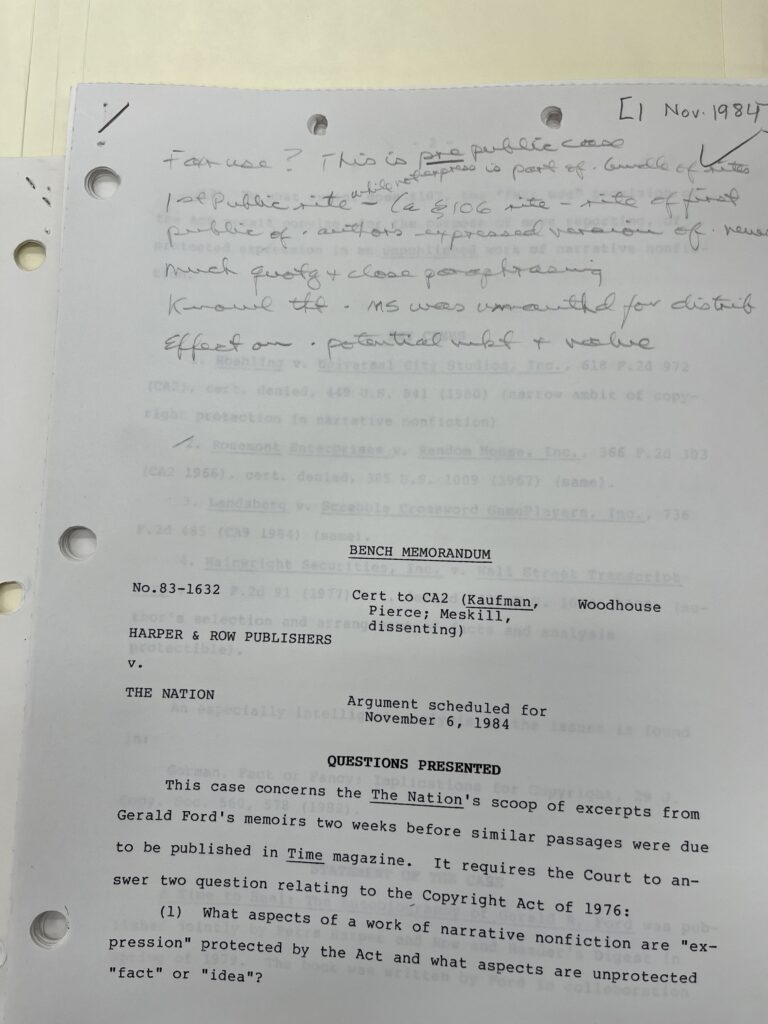

On the front page of the bench memo prepared before the November 1984 oral argument, Justice O’Connor wrote:

Fair use? This is a pre[publication] case [.] 1st public[ation] right while not express is part of bundle of rites—(a § 106 rite—rite of 1st public[ation] of author’s expressed version of news [.]

Much quot[i]ng and close paraphrasing

Knowl[edge] that the [manuscript] was unauth[orize]d for distrib[ution]

Effect on potential [market] & valueIn the bench memo’s fair use discussion, the clerk asserted: “at the risk of appearing to oversimplify the case, I believe the intentional copying of verbatim quotations from a purloined unpublished work for the sole purpose of scooping the person who purchased rights of first publication was just plain not ‘fair’ use.” Further, the memo stated that “once one accepts that the right of first publication is something of value to the author, the extent of the damage to the author that results from usurpation of that right is a valid factor to be considered under the § 107 analysis of fair use.” The memo concludes, “absent extraordinary circumstances, which were not shown here, the equities prevent copying the author’s as yet unpublished literary expression of the facts.”

The focus on the unpublished nature of the manuscript featured prominently in the November 9, 1984 Conference after oral argument, according to Justice O’Connor’s notes. Chief Justice Burger said that “these birds got this [manuscript] by larceny. They even copied directly or flagrantly plagiarized. [The District Court] had it right. This is the easiest reverse I have seen this Term. If this is fair use so is bank robbery.” Justice Blackmun stated the “prepublic[ation] was a factor to be considered.” Justice Powell said that he did not think this was a fair use because The Nation “used stolen [goods] contemptibly.” Justice Rehnquist said that he agreed “emphatically” with Justices Burger, Blackmun, and Powell on fair use: “Prepublic[ation] is an [important] factor here.” Justice O’Connor noted that she stated that “This is a first public[ation] case which is an [important] element of what is a fair use of [copyrighted] material.” She further stated “other factors here which are significant are resp[ondent’s] knowl[edge] that the [manuscript] was unauth[orized] for distrib[ution], and that public[ation] would have [a] negative effect on potential market value.” In contrast, the Justices supporting affirmance stated that the prepublication nature of the manuscript was not a major factor for them.

The discussion of fair use at Conference underscores that although judicial fair use opinions typically proceed through all four factors in an orderly way, there can be one salient fact on which the case really turns in the mind of the decision-maker. Here, that fact was that The Nation printed excerpts of a purloined copy of Ford memoir before its publication.

Justice O’Connor’s Conference notes also reveal how Justice Stevens struggled with this case. Justice O’Connor listed him as tentatively affirming. He called it a “close case.” He stated that the “fact th[a]t [it] was pre public[ation] is a signif[icant] factor in [the] anal[ysis]. There is damage here to [the] abil[ity]of [the] author to publish & [market the] work. However, [the] infringing words were mostly as to Nixon’s hospital time which was not as signif[icant]. Damage was covered mostly by [the] other parts [concerning the pardon]. Don’t know if [it] is a harmless error anal[ysis].” However, in a May 6, 1985 letter to Justice Brennan, copied to the other Justices, Justice Stevens wrote that “after wrestling with this difficult case, I have decided to change my vote and to join” Justice O’Connor’s opinion.

Justice Blackmun’s file for Harper & Row contained a copy of a December 20, 1984 memo from Justice Blackmun to Justice O’Connor requesting changes to her draft opinion, as well as her reply memo accepting most of the changes. This exchange is discussed in detail here. Justice O’Connor’s papers contain the original memo from Justice Blackmun, with (presumably) Justice O’Connor’s notation of “OK” next to almost all of Justice Blackmun’s points.

In a January 4, 1985 memo to Justice O’Connor, Justice Rehnquist expressed concern with a sentence at the end of section II of the opinion, which stated

Under the circumstances of this case, we find that The Nation’s use of the copyrighted manuscript, event stripped to the verbatim quotes conceded by The Nation to be copyrightable expression, was neither a fair use of the copyrightable material nor necessary to advance the public interest in the dissemination of information.

Justice Rehnquist acknowledged that “maybe I am being overly cautious, but I think the way you have the sentence written now could give rise to a doctrine of ‘public interest and dissemination of information’ wholly apart from the statutory doctrine of fair use.” He asked her whether she could re-work the sentence. Justice O’Connor’s papers do not contain a memo in response, but she changed the sentence at issue to read:

For the reasons set forth below, we find that this use of the copyrighted manuscript, even stripped to the verbatim quotes conceded by The Nation to be copyrightable expression, was not a fair use within the meaning of the Copyright Act.

This exchange reflects the enormous care with which Justices craft their opinions to avoid unintended consequences.

-

Although Justice O’Connor’s opinion in Feist v. Rural Telephone is probably her most significant copyright legacy, her file concerning the case is surprisingly thin. It contains no memos from her clerks, nor correspondence with other Justices apart from an exchange with Justice Scalia previously revealed in Justice Blackmun’s papers.

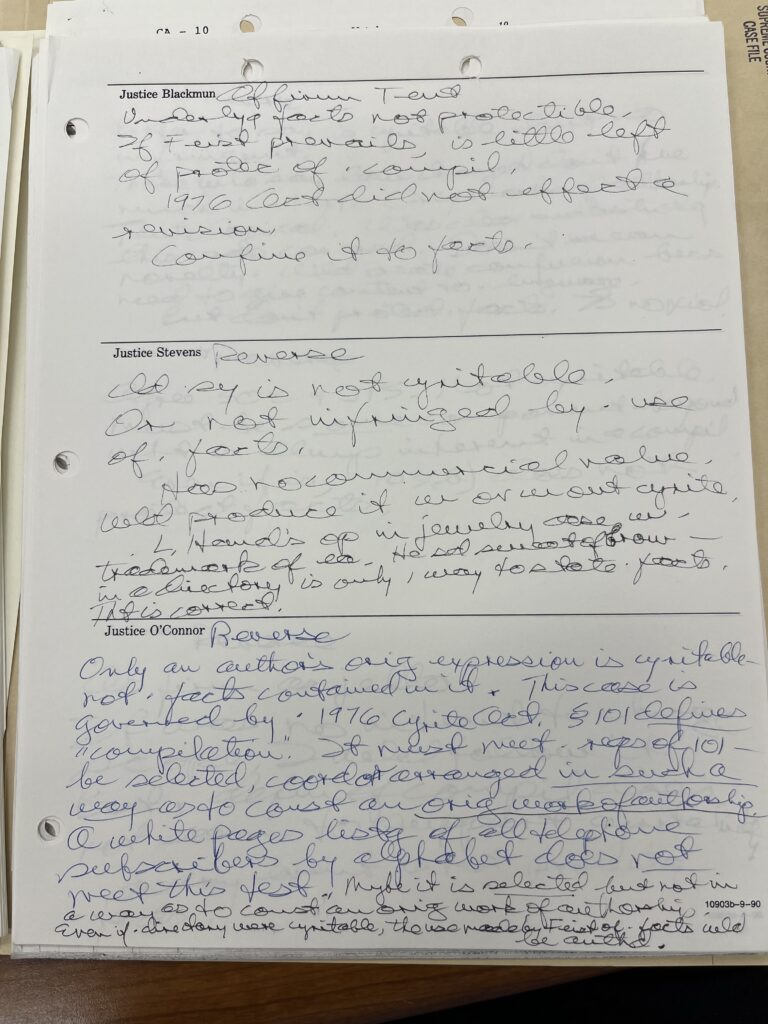

Although Justice O’Connor’s opinion in Feist v. Rural Telephone is probably her most significant copyright legacy, her file concerning the case is surprisingly thin. It contains no memos from her clerks, nor correspondence with other Justices apart from an exchange with Justice Scalia previously revealed in Justice Blackmun’s papers. The case concerned the scope of copyright protection in the “White Pages” of Rural’s telephone directory. The Tenth Circuit found that Feist had infringed Rural’s copyright when it had copied names, addresses, and telephone numbers from Rural’s directory. According to her case file cover sheet, Justice O’Connor voted against the grant of Feist’s cert. petition, along with Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justice Blackmun. However, at Conference, Justice O’Connor firmly supported reversal of the Tenth Circuit, as did the Justices who supported cert. (White, Marshall, Stevens, and Scalia). Justice O’Connor’s Conference notes indicate that the Chief Justice and Justice Blackmun tentatively supported affirmance. The Chief Justice asked whether the 1976 Copyright Act changed the scope of protection for compilations. Under the 1909 Act, a directory could be copyrightable. He added that the standard of originality was retained in the new Act. Justice Blackmun observed that “if Feist prevails, [there] is little left of protec[tion] of compil[ations].”

Justice White, tentatively supporting reversal, stated that the “defin[ition] of compilation [is] just not satisfied here.” Justice Marshall said that not every selection, coordination, or arrangement—the statutory standard—is copyrightable. Justice Stevens stressed that Rural, as the local telephone provider, was required by state law to produce the directory, so the directory would be produced with or without the copyright incentive. Justice Scalia noted that the phrase “original work of authorship” was “tautological,” presumably because a work of authorship by definition was original. He further observed that originality was not novelty, and facts could not be protected. Justice Kennedy said that copyrightability required some component beyond what is always inherent in a compilation. Justice Souter asserted that he was “as firm as jello” although he favored reversal. If there was no interest in the new Act to change the scope of protection for compilations, he would follow it and presumably support affirmance. But the definition of compilation in the new Act does not seem to support copyright protection here.

Justice O’Connor’s notes of her own remarks were the most detailed. She said that

Only an author’s orig[inal] expression is c[opyrightable], not facts contained in it. This case is governed by [the] 1976 C[opyright] Act. §101 defines “compilation.” It must meet [the] req[uirements] of 101—be selected, coord[inated] or arranged in such a way as to constitute an orig[inal] work of authorship. A white pages list[in]g of all telephone subscribers by alphabet does not meet this test. Maybe it is selected but not in a way as to const[itute] an orig[inal] work of authorship. Even if [the] directory were c[opyrightable], the use made by Feist of facts would be auth[orize]d.

These remarks at Conference foreshadowed much of her opinion for the Court—with one major exception. At Conference, neither she, nor any of the other Justices, made any reference to originality being a Constitutional requirement. While the discussion at Conference was grounded in the Copyright Act, her opinion ultimately was grounded in the Constitution. What caused that shift remains a mystery.

Justice O’Connor employed a form of shorthand in her handwritten notes