Political Ploys May Hamstring U.S. Space Supremacy

As the U.S. government moves forward with the commercialization of space, building the communication markets of the future, old-fashioned political backstabbing may stand in the way of U.S. space supremacy.

Increasingly, new entrants to the space sector find their efforts hamstrung through the bureaucratic machinations of legacy players. In recent years, both Amazon’s Kuiper and SpaceX’s Starlink products have been on the receiving end of such strategic activities.

Historically, the space industry has been dominated by government contracts and state-funded projects, making commercial operations in space a heavily regulated endeavor. The space industry is ripe for the strategic manipulation of administrative processes due to its complex nature and patchwork of regulations.

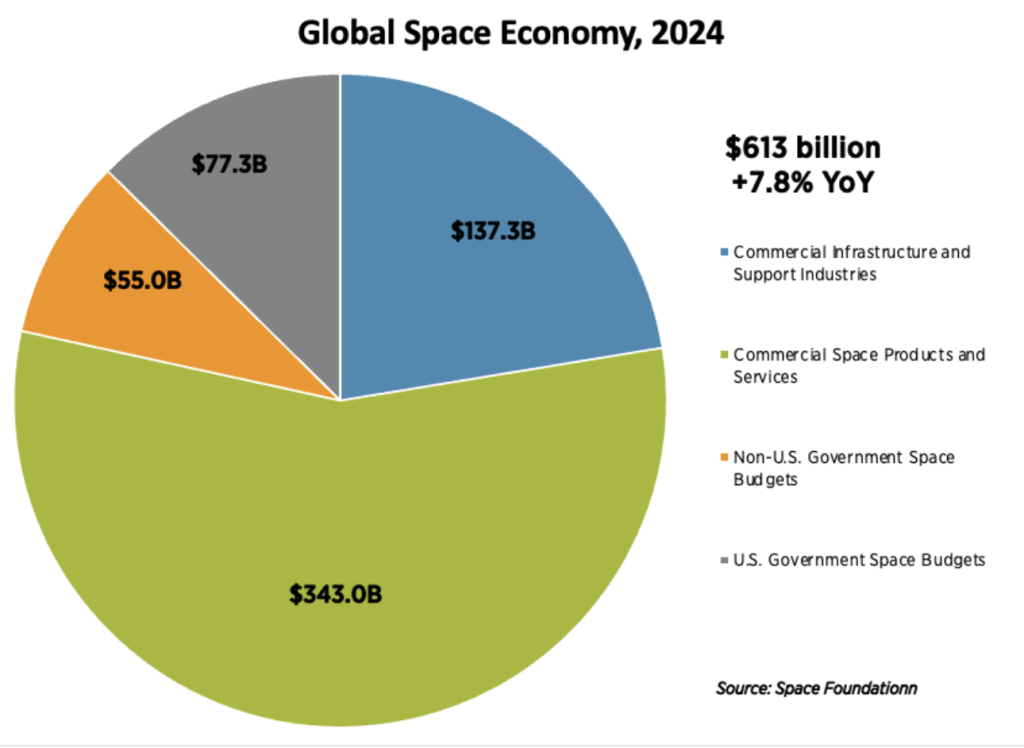

The government-centric focus of the space sector is changing, however. A breakdown of the current landscape of the space economy demonstrates the growing commercial sector. This new economy was created by projects like the Commercial Crew Program, which was a significant step toward commercial space as it helped lower launch costs.

Commercialization will bring many winners, but it is not without losers: legacy competitors. As commercial space companies like SpaceX, using newer low-earth orbit (LEO) satellites, began to disrupt the status quo, legacy players, generally using older geostationary earth orbit (GEO) technology, have pushed back. These legacy firms use a tactic I’ve previously called “swampetition”: deploying political capital and regulatory processes to hamstring rivals, rather than competing in the open market.

Though relatively new to space, this tactic is a familiar one in other sectors. Instead of improving their own offerings, businesses confronted by disruptive innovators have for centuries sought government intervention to protect their position. Efforts to distort markets through political maneuvers are as old as our understanding of free market economics: in the 1470s, Italian Renaissance monks, for example, urged leaders to destroy printers undercutting the price of scribes’ services, warning that mass production of the printed word would corrupt Italy’s youth with Ovid. In the early 20th century, trade bodies representing horse-related industries urged cities to restrict the use of automobiles, a move designed to stifle a disruptive new technology undercutting animal-based transportation. More recently, firms disrupted by tech sector innovators have urged regulators to target disruptive ‘sharing economy’ rivals. The recurring theme here is that new market entrants, particularly those making disruptive innovations, are confronted by competitors contending that regulators must hold back their rivals in the name of the public interest.

In the space context, this dynamic recurs in the struggle between incumbent GEO and disruptor LEO. These fights have played out before the U.S. Federal Communications Commission. In 2022, ViaSat, an incumbent satellite communications provider, appealed to federal courts in a battle against SpaceX’s Starlink, alleging environmental violations and “competitive injury.” However, ViaSat failed to provide specific technical risks or supporting data, and the FCC ultimately rejected the claims.

As new players like Amazon’s Project Kuiper enter the growing market for low-earth orbit broadband, strategic advocacy to regulators is increasing. Even companies that were once disruptors, now being established, are relying on political advocacy.

Kuiper’s $10 billion plan to deploy over 3,000 satellites and bring high-speed broadband to underserved communities has presented the first major competition to SpaceX’s Starlink. In response to the project, ViaSat, SpaceX, and others filed petitions to dismiss Amazon’s applications for Project Kuiper. All of these oppositions were ultimately dismissed by the FCC.

The Commission ultimately concluded that granting “Kuiper’s application would advance the public interest by authorizing a system designed to increase the availability of high-speed broadband service to consumers, government, and businesses,” but not after considerable delays, induced by the competition.

Space safety and sustainability are becoming another battleground for strategically invoking regulatory processes. Industry and government alike acknowledge the potential risk of space debris and regard debris mitigation as a crucial part of maintaining continued access to space.

At the same time, these processes can be used to trip up the competition. While SpaceX launches thousands of satellites, it also raises concerns about orbital debris regarding its competitor, Kuiper’s constellation. In 2020, the Commission approved Amazon’s Kuiper constellations. SpaceX asked the FCC for more information on Kuiper’s debris plan and continued to criticize Kuiper’s plan with ViaSat and others. While safety in space is a shared responsibility, these “safety concerns” are being used by firms to create hurdles for their competitors. Ultimately, the FCC and courts dismissed every concern raised regarding Kuiper, but not before more than three years of regulatory delays.

The strategic use of regulation is particularly concerning in the context of LEO broadband, given its significant potential for public benefit. LEO broadband is poised to connect more Americans, as 43.7 million Americans in urban, remote, and hard-to-access areas currently lack broadband. Expanding this coverage to under-connected communities could add over $29 billion annually to the U.S. GDP. The time and costs of the procedural warfare waged against Kuiper’s deployment would have been better allocated to ensuring U.S. supremacy in space.

Regulators must constantly balance public interest concerns against the strategic interests of competitive firms, and this is particularly so in the space sector, given its elaborate regulatory environment. This underscores one reason for decomplexifying the regulation of the space sector: for as long as the commercial use of space is complicated by overlapping layers of regulation, incumbent firms will have more opportunities to engage in swampetition, and slow down competitors with pretextual claims purporting to advance the public interest. This has the effect of moving conflict from the marketplace, where we want it, to the political arena, where we don’t. When firms compete in the political swamp instead of the marketplace, it can mean fewer choices, slower innovation, and higher prices.