Infographic: How Ad Dollars Are Spent

The advertising space is undergoing rapid changes as software’s expanding footprint grows ever larger. As the Consumer Electronics Show underscored yet again last week, new platforms and smarter services — phones, speakers, TVs, headsets, home appliances and other devices (even increasingly connected cars) — are bringing innovators new ad formats and new opportunities to disrupt the half-trillion dollar global advertising market. If, indeed, there is a future beyond “the end of advertising,” we can be certain that the business will not look quite the same that it does today.

Despite the accelerating pace of change, the continuing successes of Google’s and Facebook’s advertising businesses have prompted some to question whether the advertising space is still competitive. Critics of this so-called “duopoly” argue that the two Silicon Valley companies are the only viable participants in an industry that is unfriendly to incumbents and new entrants alike. These arguments paint a flawed picture of an industry that is in fact defined by constant reinvention, innovation, and new investment.

Despite the accelerating pace of change, the continuing successes of Google’s and Facebook’s advertising businesses have prompted some to question whether the advertising space is still competitive. Critics of this so-called “duopoly” argue that the two Silicon Valley companies are the only viable participants in an industry that is unfriendly to incumbents and new entrants alike. These arguments paint a flawed picture of an industry that is in fact defined by constant reinvention, innovation, and new investment.

Consider today’s reality: advertisers compete to reach the same consumers across multiple mediums. Services that deliver ads digitally to an individual’s mobile device don’t just compete against one another; they compete directly with television, print and outdoor options (e.g., highway billboards, subway stations, Times Square installations). Inter-media competition was particularly evident in last week’s “shakeup” announcement by Adobe and Mediaocean, that the two would partner to join digital ad buying with television, and “converge and automate television and video advertising.”

This competition is fierce, as advertisers continually shift budgets among platforms to maximize the return on their ad spend. What was once a quarterly or monthly re-evaluation of advertising programs has become a weekly and even a daily recalibration of how and where advertisers are reaching their audiences.

Economic research confirms that online and offline advertisements substitute for one another. This is consistent with what one would expect to find. As we’ve discussed here on DisCo before, Internet radio does compete with traditional broadcast radio — aggressively so. It would therefore be strange to suggest that advertising on digital radio doesn’t similarly compete with advertising on broadcast radio.

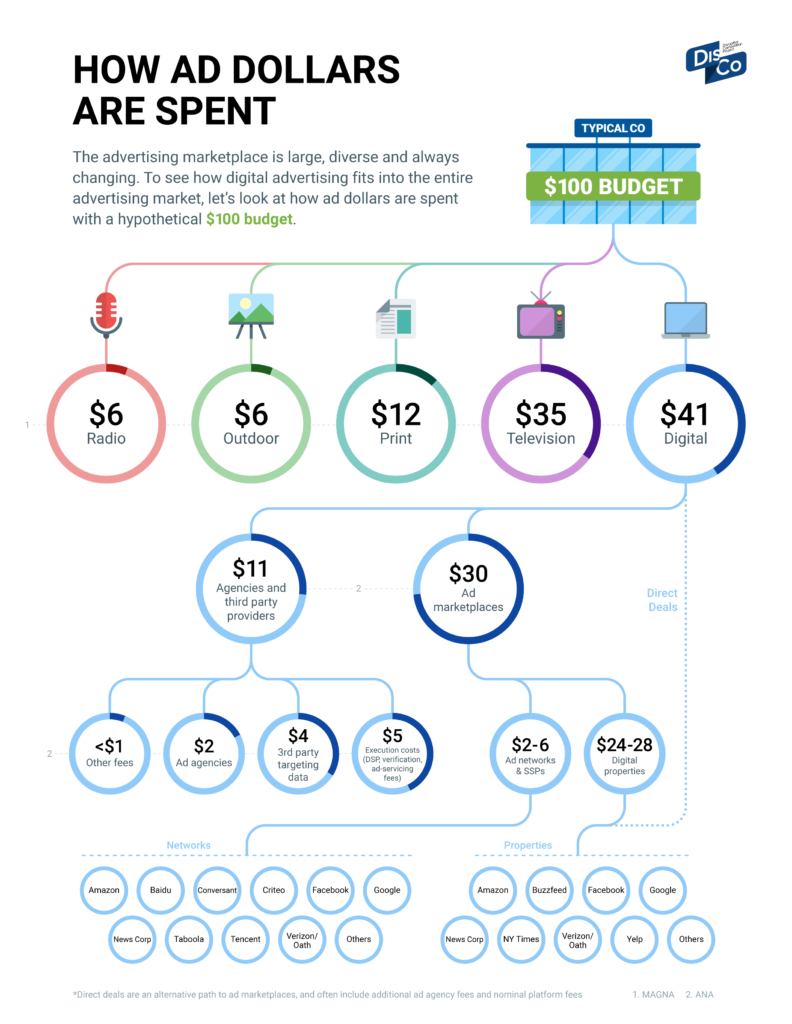

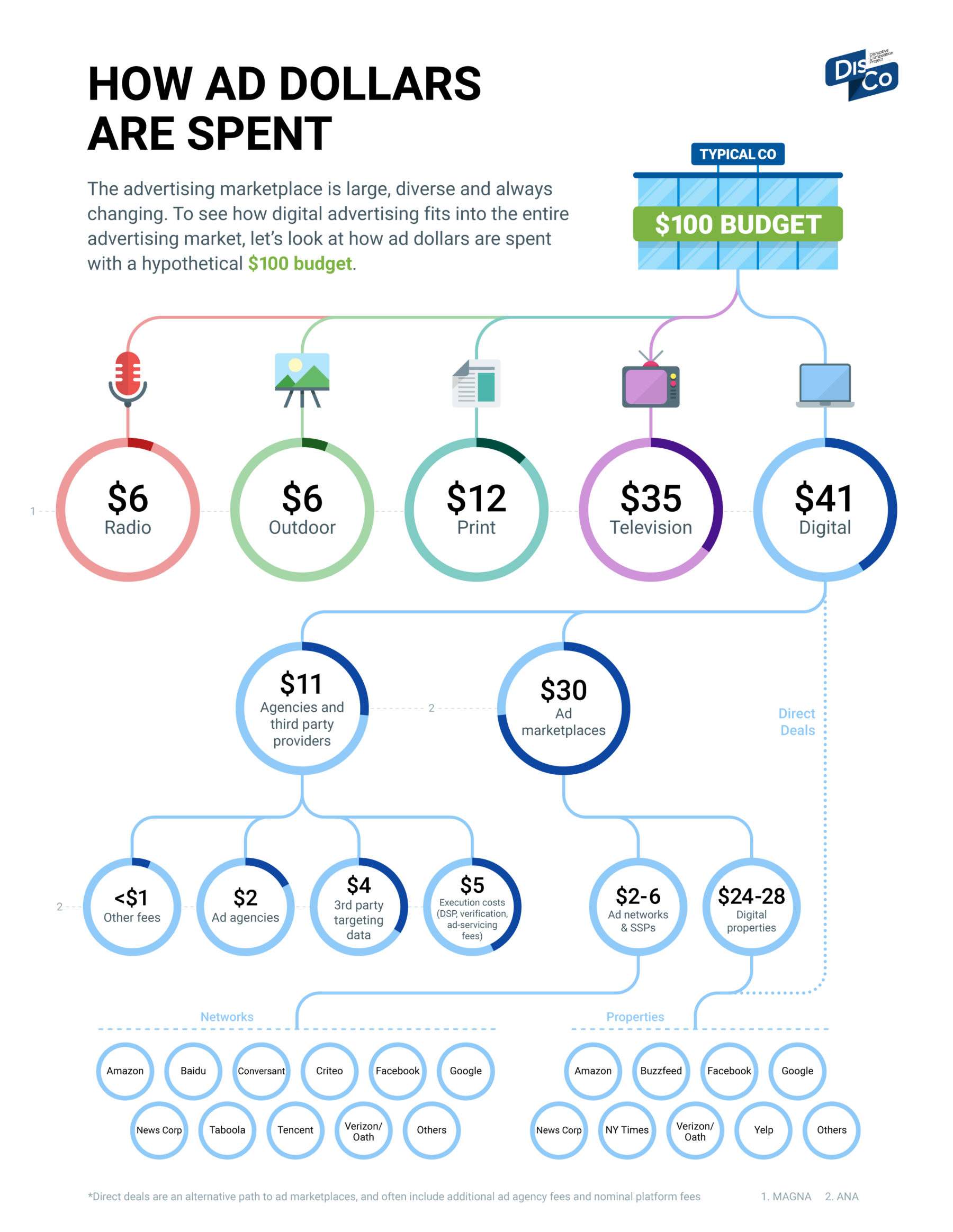

By using data from the Internet Advertising Bureau [1], [2], the Association of National Advertisers, and market research and intelligence provider MAGNA Global, the graphic below illustrates where digital advertising fits into the broader advertising space with the four other major advertising vehicles (radio, outdoor/billboards, print, and television), and represents how this categorization breaks down even further in the digital ad-supported ecosystem.

Using a hypothetical company spending a $100 budget in a fashion representative of the overall ad space, the graphic contextualizes a typical expenditure to illustrate how much ad spend goes where, rounded off to the nearest dollar. Naturally, different advertisers will pursue different strategies; a given advertiser might spend its entire budget on radio. As the graphic shows, however, an average advertiser spending a $100 budget in a representative way would spend $6 on radio.

Even after considerable growth in the online ad space, a significant number of ad dollars continue to be spent offline. Indeed, notwithstanding DisCo’s long-standing pessimism about the economic prospects of linear video programming, television advertising continues to consume a substantial share of dollars in the global advertising space: roughly 35%. The continued emphasis on television likely reflects the fact that many advertisers still prioritize reach over accuracy, and invest in television advertising accordingly. Digital advertising has recently edged out television, with an average of $41 out of every $100 dollars in ad spending going toward digital.

Of these $41 “digital” dollars, more than a quarter make their way to agencies and third-party providers, who offer services relating to targeting, verification, and execution. This leaves $30 of the ad budget for ad exchanges and platforms, including digital properties, ad networks, and assorted related service providers. (The graphic doesn’t include expenditures related to so-called “counterfeit inventory”; for more on industry’s growing efforts to fight this concern, read about IAB TechLab’s ads.txt standard.)

Facebook and Google face rising competition from others who are rapidly moving into this space. Oath, which has pitched itself as the “biggest digital publisher in the world,” is now owned by Verizon, which, like other telcos, boasts unparalleled data-driven targeting potential. Telcos such as Comcast and Charter likewise have rolled out sophisticated ad targeting products and appear ready to increase their investments in this area. Television has also shown itself increasingly subject to technological disruption: what used to be considered “linear” is increasingly digital. In addition to the Adobe-Mediaocean partnership noted above, networks from NBC Universal to Turner to Viacom have started offering new “laser focused” advertising.

News publishing companies, such as News Corp., are also making forays into the programmatic ad network business with a promise of increased brand safety — as is Digital Content Next, the umbrella trade association representing publishers, which has built what it is marketing as a “brand-safe” ad exchange. E-commerce companies are gaining traction with their own ad networks, and traditional retailers, seeing the writing on the wall, are also getting into the act. Even car manufacturers are increasingly looking like ad networks: in December, General Motors debuted an in-dash “Marketplace” enabling drivers to reserve tables at partner restaurants, order from partner coffee shops and find partner gas stations.

While advertisements on digital properties are frequently placed through advertising networks, these networks together compete for only about $2 to $6 of our hypothetical $100 ad budget. Most of the remainder accrue to digital properties on which the ads are served, that is, the apps and sites where we experience publishers’ content. This is a critical, frequently overlooked point: the vast majority of digital advertising spending goes directly to the owners of digital properties — news publishers such as The New York Times (which is nearing its goal of building an $800 million digital advertising business) and The Washington Post (which is planning an expansion after posting a profitable year); media companies such as Disney, CBS Interactive, and Verizon’s Oath division; as well as sites and apps of the kind owned by Google, Facebook, and others. (Note that it is frequently in their capacity as ad networks that Google and Facebook are sometimes claimed to “dominate” advertising. In fact, however, Google distributes 70% of its network revenues back to publishers who host its targeted ads, and has plans to exceed that percentage with new subscription tools. Estimates place Facebook in a similar range. These publisher “revenue shares” are not represented in market estimates that incorrectly assume these dollars remain with advertising networks.)

Finally, direct deals present an alternative for advertisers who would like to manually purchase ad impressions to ensure a specified volume of exposure on a particular media property, for instance the New York Times. These deals are not widely reported or easily measured (they are usually negotiated privately), but they remain an important option for many advertisers, particularly those who want guaranteed impressions on a specific publication.

Ultimately, all of the players discussed here — from measurement and third party data providers to ad agencies, television networks, and outdoor billboards — compete for a portion of the same advertising budgets. Advertisers are continuously shifting these budgets based on who provides the highest return. The rapid entry of new and established companies into digital advertising shows that ultimate power in the advertising space remains elusive in a world in which consumers’ attention is always on the move.