4K, 3D and How Perfectionism Can Crowd Out Practicality

NEW YORK–The next big thing in television resembles the last next big thing in TV.

NEW YORK–The next big thing in television resembles the last next big thing in TV.

“4K” sets–named for their almost 4,000 horizontal pixels, amounting to about four times the resolution of high-definition screens–have begun their descent out of the pricing stratosphere. The Consumer Electronics Association’s CE Week conference here put an optimistic spin on the format it prefers to call “Ultra HD,” with Sharp and Toshiba, among others, outlining plans for a major 4K marketing push.

(Disclosure: For about a year, I wrote for CEA’s blog.)

But if you step away from the undeniably beautiful picture quality of 4K as viewed up close, you see a technology that still lacks basic supporting features, may go unappreciated in many home-viewing settings and suffers from some of the same issues that now have the potential of 3D TV looking awfully flat.

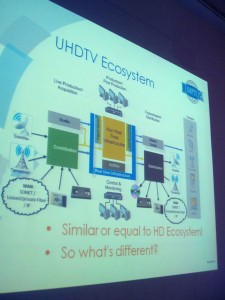

Start with two Cs: connectivity and codecs. The most under-reported fact about 4K, my own past coverage included, is that no existing 4K set includes either the HDMI 2.0 input required for a full-quality signal (the current 1.4 version maxes out at 30 frames per second, not the 60 appropriate for sports) or the ability to decode the HEVC (High Efficiency Video Coding) format the industry has anointed for 4K use.

Samsung has said it will ship an “Evolution Kit” for its existing 4K sets. Other manufacturers are leaving customers guessing.

Those problems should get solved in upcoming models, but where will you find 4K content to watch? A Blu-ray disc should have enough room for a full-length 4K flick, but that specification isn’t done yet. Cable and satellite providers could carry 4K programming, but why should they rush to set aside huge chunks of their capacity for a format so few people can watch? And there’s no standard for broadcasting 4K over the air.

That leaves online streaming. Netflix told The Verge in March that it plans to add 4K streaming “within a year or two”; it’s yet to spell out how much bandwidth you’ll need to watch that, but I’d be stunned if it it won’t need a higher-end cable or fiber-optic connection.

You can still watch existing HD content “upscaled” by software to 4K resolutions, something Sharp and Toshiba leaned on heavily in their CE Week introductions. One slide in the latter’s presentation sounded just a tad defensive: “You Don’t Need 4K Content to Enjoy a 4K TV, You Just Need High Quality 4K Upscaling.”

Ah, but will you be able to discern all of these beautiful pixels from your couch? Maybe not if your 4K budget can’t top the price of a decent used car.

While CES featured too many $20,000-ish 4K sets, CE Week emphasized cheaper but smaller sets: a $7,999.99, 70-inch set by Sharp; a $4,800, 58-inch model from Toshiba; even a 50-incher with a list price of only $1,499 from hitherto unknown Seiki Digital.

A 50-inch TV is still bigger than average, but it’s not big enough to offer a visible upgrade over HDTV from eight or so feet, a typical viewing distance. The math for optimum 4K watching, outlined in multiple CE Week presentations, shrinks that viewing distance from three times the height of the screen, as it is for HD, to only one and a half times picture height.

So for a 50-inch 4K set, you’d be supposed to sit barely three feet away. Not even Manhattan apartments are that cramped! Viewers who refrain from redecorating, however, may find themselves wondering if their new 4K set looks that much better than HDTV.

(After one industry executive compared 4K’s picture quality to “looking through a window,” panel moderator Scott Wilkinson noted that the same comparison had been made for HD: “Is this going to be like a cleaner window?”)

It all reminds me of the initial pitch for 3D television at the 2010 CES. Then as now, the hardware cost too much at first but was supposed to get cheaper–and it did. But the supply of 3D content not only hasn’t increased accordingly, it’s going to get worse. A few weeks ago, ESPN quietly announced that it would shut down its 3D channel.

That hasn’t stopped 3D from becoming an increasingly popular part of the theatrical experience. But in many homes, it amounts to a lot of surplus circuitry.

You have to ask what the industry could have done instead with the resources it sunk into 3D and is now devoting to 4K.

Unfortunately, the gadget business has a habit of focusing on one headline specification or feature at the cost of things customers actually want.

A decade ago, electronics manufacturers and record labels chased after the audiophile market with the competing, incompatible Super Audio CD and DVD-Audio formats, but the mass market wanted portability and convenience and so opted overwhelmingly for digital downloads. Blu-ray hasn’t matched DVD’s growth because online streaming offers a better renting experience (although a worse selection, courtesy of Hollywood’s “release window” rationing). Smartphone screens pack in resolution too fine for human eyeballs to detect when phone vendors should obsess over battery life.

4K’s not all bad, and at large screen sizes it should delight many videophiles. But I suspect its biggest legacy will show up on much smaller displays: that bandwidth-friendly HEVC codec, which when used on mere HD could greatly upgrade the availability of online video. And if the big-name backers of 4K don’t see that potential, I’m sure some smaller firms will jump on it first.