Insiders Fear Nate Silver’s Election Coverage Will Eat Their Lunch

There are few political junkies out there not acquainted with Nate Silver, whose blog, FiveThirtyEight, has received the kind of criticism in recent weeks normally reserved for political candidates.

What’s going on here? Why had Silver’s work inspired such debate? His analysis is unlike traditional political coverage, where quantitative data points traditionally support a more human-interest and less empirical narrative about candidates and their demographic strategies. The blog starts and finishes with rigorous analysis of objective data. Silver’s analytical successes, including impressively accurate predictions in 2008, were sufficient to induce the N.Y. Times to acquire his previously independent blog in 2010.

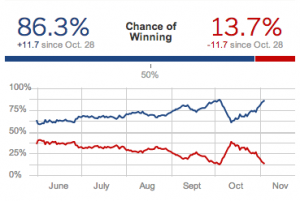

Certainly, some of the criticism comes from pro-Romney constituencies who naturally will be disinclined to embrace a non-public methodology which suggests that the race is rapidly getting away from their candidate. It is worth noting that Silver was more popular on the right in 2010, when he was correctly predicting a tide of Republican victories.

Much of the criticism, however, is from media commentators. These folks, one might conclude, aren’t defending their political leanings when dismissing statistical analysis; they’re defending their personal livelihood. We’ve seen a similar response to empirical analyses in baseball. Scott Galupo, writing for the American Conservative, notes the similarities between criticism of Silver and critics of statistically-driven baseball management as embodied in the book and movie, “Moneyball.” Galupo argues that the “old-guard recoil from sabermetrics ultimately boils down to sentiment: You can’t quantify intangibles like hustle and pluck — the ‘human element.’” (The baseball connection is not without cause: Silver’s background is in baseball forecasting.) The old-guard’s recoil, however, could and probably should be viewed as somewhat self-interested, in two aspects:

First, pundits writing ‘from the gut’ have a narrow, short term concern: if Silver has been right that the election is getting away from Romney, then horse-race coverage would be less relevant. And in the same way no advertiser spending millions on Super Bowl ads wants the game to be a blowout, news pundits and journalists who specialize in sentiment will receive fewer eyeballs in a lopsided election.

Second, and more broadly, sentiment-gauging punditry has a longer-term concern: if a technical specialist (a.k.a., nerd) aggregating publicly-available data can provide a better news product than the experience-based insider who talks to the campaigns and pundits, it will be harder for the seasoned insider to monetize their experience and access.

In response to the attacks on Silver, Ezra Klein, Poynter, and the Atlantic Wire (among others) came to his defense, with the Atlantic’s headline pretty much summing up the story: “People Who Can’t Do Math are So Mad at Nate Silver.” All of these stories are worth a read, providing variations on the theme that critics like Joe Scarborough are attacking a competitor who is disrupting the field.

“Insiders” like Scarborough, a former Congressman, offer value that derives from their experience and strong relationships with people in the inner circles of power. They are at risk of being upstaged by a data-driven blogger, who doesn’t know anybody, hasn’t worked in any Administration, and therefore doesn’t have any ‘access.’ For all we know, he might be posting in his pajamas. (Gasp!) There is a certain element of git-off-my-lawn in the criticism of Silver, as this election may be the Last Hurrah of the old-school insiders, who are being eclipsed by technical nerds using data-driven metrics, prediction markets, and other objective data to assess election outcomes.

This is not disruption in the defined sense that we frequently discuss, but it is another example of how technology-enabled competitors can threaten established, better-resourced incumbents. As we’ve said before, in many industries, incumbents respond to upstart entrants by manipulating the regulatory process to suppress them. In media industries, where at least in the United States the First Amendment reigns supreme, this is not possible. Incumbents have thus resorted to the next alternative: badmouthing.

That’s the way it should be. Tomorrow we will see who provides a better product – nerds or insiders – and markets will respond accordingly.