Of Buggy Whips, Telephones and Disruption

At the DisCo Project, we naturally focus on the current, dynamic technology marketplace and the disruption it is continuing to cause to brick-and-mortar and other “legacy” industries. But disruptive innovation is not new and not unique to high-tech. It’s been around for hundreds of years and serves as a key driver of both economic growth and social evolution.

Let’s start with the poster child of disruption, buggy whip manufacturers. In the late 19th century there were some 13,000 companies involved in the horse-drawn carriage (buggy) industry. Most failed to recognize that the era of raw horsepower was giving way to that of internal combustion engines and the automobile. Buggy whips, once a proud, artisan craft, essentially became relegated to S&M purveyors. Read Theodore Levitt’s influential 1960 book Marketing Myopia for a more detailed look.

Not everyone was obsoleted by Henry Ford. Timken & Co., which had developed roller bearings for buggies to smooth the ride of wooden wheels, prospered into the industrial age by making the transition to a market characterized as “personal transportation” rather than buggies. Likewise carriage interior manufacturers, who successfully supplied customized leather-clad seats and accessories to Detroit.

One might suspect this industrial myopia has been confined to small markets with few dominant players. But not hardly. One of the more famous series of patent cases in history were the battles between Western Union and Alexander Graham Bell in the 1870s, where the telegraph giant (along with scores of others) vainly tried to contest Bell’s U.S. patents on the telephone. Ironically, the telephone was initially rejected by Western Union, the leading telecommunications company of the 1800s, because it could carry a signal only three miles. The Bell telephone therefore took root as a local communications service simple enough to be used by everyday people. Little by little, the telephone’s range improved until it supplanted Western Union and its telegraph operators altogether.

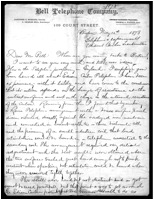

Apart from scurrilous character assassination suggesting Bell had bribed U.S. Patent and Trademark Office clerks to stamp his patent application first, the patent cases are best remembered for their eventual 1879 settlement. Western Union assigned all telephone rights to the nascent Bell System with the caveat that Bell would not compete in the lucrative telegraphy market. After all, Western Union surmised, no one wanted to have their peaceful homes invaded by ringing monsters from the stressful outside world. Check out this verbatim 1876 internal memo from Western Union:

Apart from scurrilous character assassination suggesting Bell had bribed U.S. Patent and Trademark Office clerks to stamp his patent application first, the patent cases are best remembered for their eventual 1879 settlement. Western Union assigned all telephone rights to the nascent Bell System with the caveat that Bell would not compete in the lucrative telegraphy market. After all, Western Union surmised, no one wanted to have their peaceful homes invaded by ringing monsters from the stressful outside world. Check out this verbatim 1876 internal memo from Western Union:

Messrs. Hubbard and Bell want to install one of their “telephone devices” in every city. The idea is idiotic on the face of it. Furthermore, why would any person want to use this ungainly and impractical device when he can send a messenger to the telegraph office and have a clear written message sent to any large city in the United States?

Epically wrong! But that, of course, is the challenge of disruptive innovation. It forces market participants to rethink their premises and reimagine the business they are in. Those who get it wrong will be lost in the dustbin (or buggy whip rack) of history. Those who get it right typically enjoy a window of success until the next inflection point arrives. Were barbers out of business when, some 200 years ago, doctors began to curtail the practice of bleeding patients, eventually usurping barbers as providers of health care? No, because barbershops moved from medicine to personal grooming.

Disruptive technologies create major new growth in the industries they penetrate — even when they cause traditionally entrenched firms to fail — by allowing less-skilled and less-affluent people to do things previously done only by expensive specialists in centralized, inconvenient locations. In effect, they offer consumers products and services that are cheaper, better, and more convenient than ever before. Disruption, a core microeconomic driver of macroeconomic growth, has played a fundamental role as the American economy has become more efficient and productive.

Clayton Christensen, Thomas Craig and Stuart Hart, The Great Disruption

There are hundreds or thousands more examples we can discuss. Polaroid and Kodak, both innovators in their own right, have faced bankruptcy and virtual irrelevance over the past few years because they could not cope with rapid disintermediation of their photography businesses by digital technologies. Walgreens, CVS and camera shops, meanwhile, have retained a solid photography revenue stream by supporting photo printing from SD cards and even Facebook photo collections.

Some businesses get it and some do not. Disruptive competition drives out those whose world view tries quixotically to preserve the past or to protect economic and social customs from technology-driven change. Disruption is of course not a panacea for all social ills; New Yorkers, for instance, complained as much about the filth and stench of cobblestoned city streets filled with horse droppings in the 19th century as they did about the filth and stench of paved streets filled with cars and CO2 fumes in the 20th century. As an economic and competitive matter, however, disruption is a process of continually “out with the old and in with the new.” And it’s been that way for as long as anyone can remember.