Today’s FCC Action on Cable Boxes, 20 Years in the Making

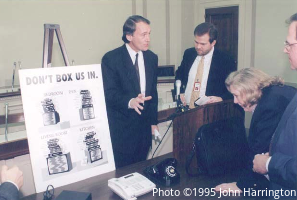

Then-Congressman Ed Markey (D-MA), in 1995, saying that consumers shouldn’t be “boxed in” by their cable companies’ high leasing fees and clunky equipment. Not much has changed in the 20 years since.

It’s been 20 years since Congress decided that the set-top box market needed a competitive jump start. The Congressional debate around the introduction of the 1996 Telecom Act, and associated legislation, made that much clear. Just ask Sen. Ed Markey (D-MA).

Two decades ago then-Congressman Markey (see video below) and former Republican House Commerce Committee Chairman, Tom Bliley (R-VA) led the charge on promoting competition in the set-top box marketplace with a bill that became part of the Telecommunications Act, which marked its 20th anniversary last Monday. Back then, Bliley said that:

[Their bill] seeks to ensure that we follow the competitive market model rather than the monopoly model. . . . A consumer should be able to choose [a set-top box] the same way he or she chooses other products, by going to the store, comparing the quality, features, and price, and buying or renting the best one.

The Telecommunications Act of 1996 directed the FCC to

[A]dopt regulations to assure the commercial availability . . . of converter boxes, interactive communications equipment, and other equipment used by consumers to access multichannel video programming and other services offered over multichannel video programming systems, from manufacturers, retailers, and other vendors not affiliated with any multichannel video programming distributor.

Twenty years later, not much has changed in the dynamics of the market for set-top boxes as the vast majority of consumers still lease boxes from their cable providers.

Since 1996, the FCC has tried to promote competition in different ways. First, in 1998, the FCC instituted the “integration ban,” which required that pay-TV providers separate a set-top box’s security functions from its tuning and navigation functions (i.e., channel changing), which had previously been integrated within the set-top box. The idea was that a competitive market could develop if a consumer could buy a device at retail that would be able to access the pay-TV signal and content via a standard mechanism that would perform the necessary security and authentication functions. Pay-TV providers could still lease set-top boxes to customers, but their boxes would have to utilize the same security mechanism as a third-party device.

The integration ban led to a long process where the cable industry ultimately developed CableCARD, which could be inserted into a television or set-top box and perform the security function that would decrypt the pay-TV signal. CableCARD was supposed to promote a competitive retail market because a third-party device could use the standardized CableCARD to decrypt a pay-TV provider’s signal. For example, if a consumer moved to an area with a different cable provider, the set-top box that she purchased could still access the new provider’s signal as long as it had a CableCARD to decrypt the signal.

However, the retail market didn’t develop as hoped. DisCo contributor Glenn Manishin detailed some of the problems with the FCC’s actions after 1996 and the development of CableCARD, but one of the major reasons why a vibrant market did not come about is that pay-TV providers did not have any incentive to move past their leasing regime, which provided a steady and substantial source of revenue. The incumbent cable industry controlled the CableCARD standard setting process, and they were able to set up arbitrary hurdles preventing consumers from utilizing third party options. Furthermore, CableLabs, the research and development arm of the cable industry, had to certify competitive devices before they could go on the market and compete with cable’s own proprietary set-top boxes. Unsurprisingly, the process was burdensome, expensive, and subject to gaming by the cable industry. This problem was noted by Timothy Lee at Ars Technica:

[T]he companies developing the standards had a vested interest in seeing them fail. Cable incumbents prefer to have customers use their own proprietary set-top boxes. This gives them maximum control over the customer experience—and, as a consequence, maximum influence over the customer’s wallet.

Unsurprisingly, the standards produced by this process haven’t worked well. The first-generation standard, called CableCARD, included a DRM scheme that required device manufacturers to submit to a burdensome certification process run by CableLabs, a consortium of cable companies….

[Steve Schultze of the Center for Information Technology Policy at Princeton] said that cable providers have used the control provided by CableCARD to discourage the introduction of new devices. A number of devices, he said, had been “stuck in the certification queue.”

CableCARD’s implementation was so poor that in 2011 the FCC stepped in and set some very basic rules of the road for CableCARD devices. The FCC had to mandate that pay-TV providers give consumers accurate information on the provider’s website about the cost of renting a CableCARD, billing inserts, or even when consumers can call; that providers not charge subscribers for using their own box; that providers allow subscribers to self-install CableCARDs into their own devices; and that if a subscriber opts for installation by the provider’s technicians, that the technician must bring with them at least as many CableCARDs as the subscriber requested. The poor implementation, obstacles to installation, and resulting confusion have prevented a fully competitive market from developing.

Fast forward to today — twenty years after the 1996 Act directed the FCC to pave the way for a competitive market — an overwhelming number of consumers are still leasing set-top boxes from their pay-TV providers. Last summer, Senators Markey and Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) released the results of a study noting that 99% of customers lease set-top boxes from their cable providers. Breaking down that percentage, in its most recent Commission-mandated filing regarding the status of CableCARD deployment and support, the National Cable & Telecommunications Association (NCTA) noted that since 2007, the nine largest cable operators have deployed about 617,000 CableCARDs for use in retail devices that consumers have bought, but that pales in comparison to the over 53,000,000 CableCARDs the cable operators have deployed in their leased devices.

That 99% number is nothing new. Based on NCTA’s numbers, the amount of subscribers leasing set-top boxes from their providers has actually increased over the past decade. By the end of 2008, the top ten operators had deployed 392,000 CableCARDs in retail set-top boxes, but they had deployed over 9,766,000 CableCARDs in operator-supplied set-top boxes since the “integration ban” went into effect on July 1, 2007. The top ten providers served about 90% of all subscribers at that point. So by the end of 2008, 96% of subscribers leased a box from their provider. In 2012, NCTA reported that the top ten MVPDs had deployed 554,000 CableCARDs for use in retail devices, but they had deployed more than 32,000,000 operator-supplied set-top boxes. The percentage of subscribers leasing set-top boxes from their provider climbed to 98.3%.

With 99% of subscribers now paying rental fees every month, these set-top box lease fees remain a significant source of revenue for pay-TV providers. Cable rates have already increased at more than double the rate of inflation (6.1% annually from 1995 to 2013 while the CPI rose 2.4% during the same period). They have also focused on the set-top box for more revenue. For example, just a few weeks after New York approved the Charter-Time Warner Cable merger, Time Warner Cable announced that it would increase leasing fees on its HD set-top boxes from $6.98 a month to $8.50 a month. The Consumer Federation of America and Public Knowledge found that pay-TV providers are overcharging consumers between $6 billion and $14 billion every year, and “[t]oday, the average charge for a set top box is $7.43 per month, an increase of 185% since 1994.” Note, consumers are often stuck with the same antiquated box long past its useful life, and cable providers also very rarely provide updates to their set-top boxes’ user interfaces, unlike iOS and Android, which provide free upgrades much more frequently. It’s telling that a recent poll found: “77 percent of Americans believe pay-TV companies care more about profit than quality service.”

This brings us back to 20 years ago. Back then, Congress recognized that consumers should be able to access a competitive, retail market for set-top boxes. However, two decades later, 99% of consumers lease a set-top box from their provider, amounting to $19.5 billion in revenue for the cable industry. And those leasing fees are only increasing every year, usually for the same equipment consumers have had for over five years. Though there have been great innovations along the way (e.g., the DVR, integrated search, and now voice remotes), this is still one of the last areas of consumer electronics where consumers and device manufacturers are subject to gatekeepers — the cable industry. Undaunted, Senator Markey and Congresswoman Eshoo (D-CA), who was also a key supporter in 1996, are still leading the charge for opening up this market to competition. With its vote today on Chairman Wheeler’s proposal, the FCC has a chance to finally “assure the commercial availability” of third-party set-top boxes.