Apple, Samsung, & Design Patents: Is More Necessarily Better?

Over at Patent Progress, Matt Levy points out the potentially ridiculous task that might befall U.S. Customs: deciding ‘how round is round?’, should an ITC administrative law judge call upon the agency to prevent Samsung smartphones from entering the country based on infringement of Apple’s “rounded rectangle” smartphone design patent, which I have previously criticized.

The potential dilemma for Customs illustrates how problematic the patent expansion is proving to be. I am reminded of discussions from Stanford Law’s recent conference, Design Patents in the Modern World, perhaps one of the first gatherings focused specifically on this once-sleepy area of the law. The great unanswered question of the April event was: is this all worth the trouble?

Design patenting has generally focused on physical goods, or ‘hardware.’ Apple’s rounded rectangle design falls within that category. There is nothing inherently wrong with the subject matter of a smartphone for a design patent. Indeed, aesthetic curves on a hand-held object harken back to some of the most iconic design patents, such as the Coke bottle. The problem here is that design patents protect aesthetically pleasing, but non-functional design choices. As I have previously argued, and some courts have agreed, removing sharp corners from something you put in your pants has a functional purpose. It isn’t about aesthetics, any more than a steering wheel airbag is ornamental. In this vein one might also place Nokia’s equally simple, recently received rectangle with circular sides.

To complicate matters further, even as aesthetics and functionality blur, the subject matter of design patenting has grown. Design patenting is no longer limited to “articles of manufacture,” and now reaches into all corners of commercial aesthetic decision-making, including software user interface design. Several conference participants voiced concerns regarding this sweeping expansion, noting that it isn’t clear that the costs are outweighed by benefits.

The fact is, we don’t have good data to know if the current system is worth the administration costs. A fellow panelist, for example, argued that we needed expansive design patents to protect the amazing innovation that we’ve in smartphones, suggesting causality. Innovation followed high protection, hence, it works. Or so went the argument.

My response was that it requires a certain measure of faith to assume that the exceptional remedies in design patents, legislated in 1880s, were the proximate cause of a surge in innovative smartphone design over 100 years later. If we’re assuming correlation is causation, I argued, then one could just as easily posit that this current era of smartphone innovation resulted from the fact that the USPTO moved to far nicer digs in Alexandria in 2005, which improved morale and thereby U.S. innovation. The event correlates far more contemporaneously; so it is an equally valid hypothesis. At least until someone points to a nation with third-rate innovation but a blinged-out patent office.

Ultimately, the point of this mostly facetious argument was that in order to make generalizations about the innovation-inducing nature of an IP system, we need a natural experiment.

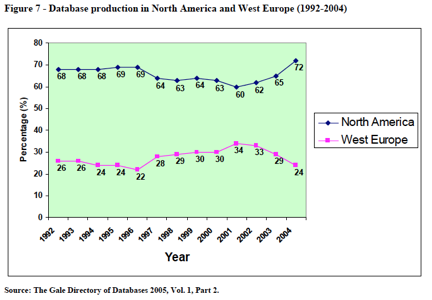

What would a natural experiment look like? We have Rule A in two jurisdictions, and then one of them switches to Rule B, which creates more IP rights. Then, we evaluate what happens. One of the more prominent examples of this – noted years ago by Duke law professor James Boyle – was the European Database Directive in 2000, which created sui generis rights in databases. The U.S. Congress, on the other hand, had the option to do so in the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (and subsequently) but declined to do so, no doubt due in part to aspects of the Supreme Court’s Feist decision, which ‘constitutionalized’ aspects of copyright law.

So what happened with databases? After a brief spurt of post-Directive activity in the European database industry, that industry promptly tanked; Europe’s share of the global database market plunged relative to the U.S. share. The European Commission’s own report shows a marked decline, as depicted in the chart below.

If the more-is-better approach hobbled databases, can we be certain it won’t do the same to industrial design?