Documentary Evidence: A Director Opens Up About Distribution, Gatekeepers and Piracy

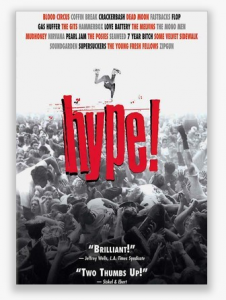

Traveling to Seattle a couple of weeks ago for work got me thinking anew of one of my favorite documentaries from the 1990s: Hype!, a smart and funny unpacking of how the grunge music scene in Seattle first became A Thing and then a thing to be commercialized.

Traveling to Seattle a couple of weeks ago for work got me thinking anew of one of my favorite documentaries from the 1990s: Hype!, a smart and funny unpacking of how the grunge music scene in Seattle first became A Thing and then a thing to be commercialized.

So once I got home, I wanted to watch this 1996 flick again and then discovered I couldn’t just cue it up over the Internet. Not on Netflix streaming, not via Amazon Instant Video, not at iTunes, not through Hulu Plus–although Amazon did offer to hook me up with a VHS copy.

So I did what any Internet-savvy movie fan might do. No, not fire up a BitTorrent client: I looked up the movie’s director, found one of the production companies he’s worked for, and asked a publicist to pass on my query about its unavailability.

Doug Pray promptly responded. “The simple answer to your question is that our 14 year license just ended with Lionsgate, so we are in transition for a few months,” he wrote. That left only a dwindling inventory of physical copies of Pray’s directorial debut: “If I had any extra DVD’s I’d mail you one personally.”

Our subsequent e-mail conversation only covered the business issues of one guy in the movie industry. And yet it was still a lot more illuminating than the incumbent-oriented take you might get from somebody tasked with representing an entire market.

The first thing to know is that Pray doesn’t miss the old way of doing business: a premiere at a film festival hopefully led to a distribution deal, the flick made its way into a subset of theaters, and then positive reviews finally got it into home video, where the director might finally net a profit.

Today, the path from directors to viewers isn’t so linear. Pray credited Netflix, Amazon and iTunes as “probably the most meaningful three markets for an indy film” but also said the increasing number of film festivals “have become a sort of non-profit form of promotion and distribution.”

(Like any good freelancer, Pray has multiple sources of income; he also does commercial work on the side.)

But that doesn’t mean that directors have been liberated from the traditional dependence on distributors–even if it’s one many filmmakers consider “difficult to assess, filled with questionable accounting, and rarely cost-worthy to audit.”

“I’d never have the time or ability to negotiate separate deals with the Amazons, Netflix’s, and iTunes out there myself,” Pray wrote. “Gotta have a distributor do it.”

In an interview in 2011, he shared considerable sympathy for the middleman, calling documentary distribution “a thankless, difficult chore in a nearly impossible market with a terrible, horrible history of financial success.”

The potential upgrade for a creator is not in firing the old gatekeepers but finding better ones. He cited “a new universe of do-it-yourself marketing and distribution companies out there that are being used by more and more indy filmmakers: Tugg, Topspin Media, and others.”

Here, I started thinking Pray should have been at XOXO two weeks ago for that weekend-long conversation about sustainable independent creativity.

But what about all those people downloading or streaming movies without paying?

“Every filmmaker and producer cares about whether or not their movie is selling, how much, where, when, and they also care if it’s being pirated,” he wrote. But that’s not the end of the story, as he noted when recounting how his 2006 release Infamy got thrown up on YouTube as separate segments.

Instead of being upset (“the odds of me seeing money on the deal were slim”), he left those clips alone. While writing that “kids willing to watch a crappy YouTube video aren’t likely to order a DVD by mail,” Pray also noted the potential advertising benefits for a movie later carried on Showtime.

Indeed, there’s evidence that even habitual copyright infringers spend generously on content. I hope Pray doesn’t have to wait too long to see Hype benefit from some of that expenditure.