Yes, Android Updates Are A Mess. What Do We Do About That?

The American Civil Liberties Union has a gripe with an unusual subject: the software on your Android phone.

The American Civil Liberties Union has a gripe with an unusual subject: the software on your Android phone.

It filed a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission on Tuesday that asked the FTC to investigate the major wireless carriers’ slow delivery of security and other updates to Google’s operating system, then compel those companies to let customers walk if their phones don’t get those patches soon enough.

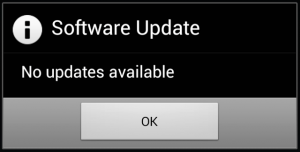

The call for the FTC to research this situation looks a little redundant: Thanks to the astute reporting of Ars Technica’s Casey Johnston and Computerworld’s J.R. Raphael, among many others, we already know that Android phones get updates months after Google releases them, if they arrive at all. Meanwhile, almost all new models continue to ship with the 4.1 Android release that dates to last summer–not the 4.2 version that Google released in November.

But maybe having a government stamp on this will get more people’s attention.

What’s less obvious is how much late or never-shipped security updates will expand the market for malware on phones. At a minimum, this makes life easier for crooks looking to make a few quick bucks off unsuspecting Android users. At worst, I worry that unpatched vulnerabilities will allow compromises of the authentication apps used in many sites’ implementations of two-step verification.

(I asked about that concern at a discussion about user-account security at Google’s Washington offices yesterday. The gist of Google engineer Mayank Upadhyay’s reply: “This is a problem we are definitely aware of.”)

I’m more interested in the ACLU’s proposed remedies. In the filing, Christopher Soghoian and Ben Wizner call for the commission to require carriers to disclose “the existence and severity” of unpatched Android vulnerabilities on phones they sell; subscribers whose phones don’t get “prompt, regular security updates” could either bail on contracts without paying early-termination fees or demand a replacement phone for free.

In the abstract, delayed software updates looks like the kind of problem that’s easier to attack in a lawsuit against an egregious offender than to prevent with a law that would govern the entire industry.

If, for instance, you require that every new phone be provided with software updates for the next two years, that risks discouraging startups from getting into the business at all. And what counts as fast enough, when testing by carriers and manufacturers always imposes some lag time?

The worst delays apply to major updates to Android. Gizmodo’s Brent Rose reported that it takes phone chipmakers a month or two to write basic code wiring their hardware into each new major Android release, after which manufacturers may need six to eight weeks to update their own layers of software–and then carriers can take three to six months testing all these updates for compatibility with their networks.

The ACLU complaint repeatedly calls for “prompt, regular” security updates but doesn’t define those two words. In an e-mail, Soghoian didn’t get more specific: “If the carriers were just a few weeks, or a month behind Google, we’d never have filed the complaint.”

Letting the customer decide when they’re annoyed enough by late updates to demand satisfaction might not give carriers upfront guidance as to what would be prompt enough, but presumably they would learn once they had to let a sufficient number of people out of a contract or give them free replacement phones.

Or would they? Remember, these customers have kept on buying Android phones even after the pattern of delayed or nonexistent updates has become embarrassingly obvious.

I would not be surprised if the FTC instead chose to make examples of some carriers or vendors. In one under-reported way, it already has: Its February settlement with HTC over a series of Android privacy and security vulnerabilities included a specific, strict timeline to ship patches for those flaws within 30 days of the order.

In the long term, a better fix would be to get the carriers out of the critical path of phone procurement–in other words, have the U.S market be more like those in much of the rest of the world, where people can buy phones direct from the manufacturer, with much clearer accountability.

But aside from the recent, refreshing exception of T-Mobile’s switch to unsubsidized pricing, that’s not economically viable for most consumers: The other big carriers don’t give you a discount if you bring your own phone; in some cases, they may not even let you bring your own phone and have it activated. So you have to wait to get your update, if it ever arrives, while a fundamental customer feedback loop stays needlessly tangled.